Veins of Porcelain: Brickwork Beneath the Aurora

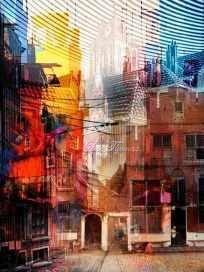

Veins of Porcelain: Brickwork Beneath the Aurora reimagines Johannes Vermeer’s The Little Street as a radiant fusion of memory and motion, where brick walls pulse with color and rooftops shimmer with urban electricity. The warm reds of Delft are layered with auric yellows and sharp teals, transforming domestic architecture into a visual echo chamber. Vermeer’s quiet figures remain, half-submerged in time, while cathedral towers and light distortions weave a dream of city-life remembered. This reimagination elevates a simple street into a living archive—where every surface hums with history, and every brick remembers.

Please see Below for Details…

Hotline Order:

Mon - Fri: 07AM - 06PM

404-872-4663

Veins of Porcelain: Brickwork Beneath the Aurora reimagines Johannes Vermeer’s The Little Street as a symphony of architectural memory and chromatic emotion—where the domestic solidity of 17th-century Delft melts into a pulsating dream of fragmented cityscapes and cascading light. The scene, once quiet and content in its stillness, is now caught in the prism of urban recollection, split between memory and motion, permanence and flux. The reconfiguration is not a distortion, but an elevation—Vermeer’s domestic row becomes a passage through time, stained by light, rhythm, and longing.

Vermeer’s original painting offered us a tender vision of everyday life—two women absorbed in their domestic routines beneath weathered gables and worn brick. Here, that brick is no longer static. It breathes, it pulses, it warps like film exposed to sun. The rooftops shimmer in cathedral pinks, while their edges are sliced by electric lines of distortion—hints of circuitry, of modern interruptions that fracture the serenity of the past. The warm, rustic reds of the original façade have expanded into a full symphonic range: blood-orange, amber, cherry-gold, juxtaposed with a cold wave of teal and indigo. These are no longer just buildings—they are melodies in color.

The upper half of the work unfolds like a city remembering itself. A cathedral tower looms ghostlike in pastel haze, spectral yet majestic, echoing the deep-rooted spiritual architecture of memory. Horizontal striations stretch across the entire scene, as if recalling the static of an old television, or blinds casting prison-bar shadows over a dream. These lines create a cinematic tension—are we watching the past, or is it watching us?

To the left, an echo of urban neon emerges—blues and violets that should not exist in Vermeer’s world—but here, they belong. Their fluorescence smudges into the reds, contaminating the quaint with the technological, the nostalgic with the electric. The yellow burst near the top-left seems to explode like a dawn, not just of sun, but of consciousness, washing down the walls and windows of the neighborhood like a revelation.

As the artist, my thought while reimagining The Little Street was to dissolve the threshold between memory and architecture. I’ve always believed buildings do not merely stand—they record. The bricks remember fingers that scrubbed them clean, children who leaned against them, wars they survived, and lovers they listened to through open windows. In this reinterpretation, I did not want to simply depict a house—I wanted to unveil the vibrations it has absorbed over centuries, the energies of lives lived quietly and forgotten completely. Vermeer’s street is no longer still. It is humming with the hum of remembered heat.

The color palette was crucial to this transformation. Reds were chosen not just to mirror the original brick, but to evoke bloodline and inheritance—what is passed down not in words, but in walls. The electric blues slicing across the rooftops invoke the presence of modernity—like spectral graffiti on the body of history. Bright yellows disrupt and warm in equal measure; they form halos over rooftops, windows, and pathways, making ordinary corners feel sacred. The lower portion, anchored in heavier shadows and faded neutrals, suggests the grounding force of reality—a reminder that all transcendence must stand on something solid.

And then there’s the human presence. Vermeer’s women are still there—but they are now almost submerged, like fossils in the coral reef of memory. They sit quietly in the lower right, still performing their daily chores, but now beneath the grandeur of city-light and fractured glass. Their presence, softened and ghosted by time, reminds us that while the city pulses upward and outward, it is the small gestures—the act of sweeping, the quiet pause in a doorway—that shape the soul of a place.

This surreal homage does not aim to erase Vermeer’s gentle gaze—it honors it by imagining what happens when that gaze ripples outward. When the quiet intimacy of home is turned inside out and painted across the architecture of the soul.

Add your review

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Please login to write review!

Looks like there are no reviews yet.